ALUMNI: At 96, Oldest-Living CJC Graduate has Stories to Tell

By Lenore Devore, B.S. Journalism 1984

Allen Alexander was a sophomore at the all-male University of Florida when Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941. The then-history and political science major remembers that Sunday, and the next day, when he was talking with several students about how long they thought the war would last — six days, six months, six years.

“We had no idea,” recalled Alexander, B.A. Journalism 1945. “Warren Felkel, a physics major, said all bets were off if a nation develops an atomic bomb. We had never heard of that. He explained atomic energy. It truly was an eye opener at the time.”

The war prompted Alexander, the oldest living graduate of the College, to take a year off from College. The experiences he gained during that year led him back to UF to get his degree.

Born on Feb. 22, 1923, Alexander grew up in Flushing, N.Y. During the winter of 1939, his family moved to Punta Gorda, Florida, where he graduated from high school. At the time, any male high school graduate in the state could attend UF. But he decided to return to New York for the summer.

“Then I said, ‘I need to go to college,’ ” Alexander said. “I sent a telegram on a Tuesday asking UF if I could enroll. They said yes, but the deadline is Saturday at noon. That gave us just enough time for me to get bundled up, get a suitcase and a shoebox full of sandwiches. I got on the train. I arrived in the middle of Gainesville, population about 15,000, at 10 a.m. Saturday. UF enrollment was about 3,600. I got in.”

At the end of his junior year, he decided to leave UF and landed a job with the Associated Press Photo Library at Rockefeller Center in New York. “Every day we got cartons of photos from all over the world, mostly the war zones. We had to store photos so you could retrieve them.”

While working there, he met people in the newsroom, including bureau chief Sam Blackmon, whom he told he wanted to become a reporter. Blackmon said: ‘When you get your degree in journalism, send me a letter and I’ll look at it.’ ”

Alexander returned to UF, where he changed his major to journalism. Because most students had left college to fight in World War II (he was in ROTC but couldn’t pass the physical to enlist), class sizes were small, about five students each. “Instruction was intense. You couldn’t duck it. Looking back at it, I was fortunate,” he said.

He recalls two journalism professors who had an impact: Elmer Emig and Bill Lowry. ”Emig was more of an editorial writer. Bill was a hard-crusted reporter you see in the old news reels.”

At 96, his memory is intact. He recalls laying out The Alligator in an upstairs office at the Gainesville Sun when “the editor came running up yelling, ‘FDR has died. Roosevelt is dead.’ It was shocking. He had been president for so many years.”

Not all memories are from the classroom. He said back then, ROTC emphasized horse-drawn artillery, and they got horses from Fort Riley, Kansas, where they played polo. “If the horse couldn’t cut the mustard, we got it,” he said. The horses pulled 75 mm cannons. “We had the largest group of horses for an ROTC. I was a good horseman because my parents actually rented a horse during several summers at our country home in upstate New York. On the weekends at UF, we could take the horses out for maneuvers where the stadium is now. It was woods back then. We had a lot of fun.”

Alexander played baseball, basketball and ran track in high school — the fastest sprinter at Punta Gorda High School. He joined the track team his freshman year at UF. “I had always been very fast” in short distances, like the 40-yard dash, he said. But he had very low endurance, so UF put him on the relay team. His body couldn’t take the constant practicing, so he left the team.

He was also a member of the International Relations Club, which was led by three political science professors whom he said were great teachers: “Wild Bill” Carleton, Manning Dauer and Claude Hawkins. “They were great guys and they don’t know how much I owe to them.”

He worked in the UF library, making about 25 cents an hour. “I remember the chief librarian quite well: Nelle Barmore. She would put two fingers from each hand in her mouth and whistle, then say, ‘Now hear this.’ She ran that library after (the former head librarian was drafted). She was a character and ran a good library.”

On warm nights, he had fun skinny dipping in a pool or pond, he can’t remember which, in the middle of campus. “The groundskeeper would go down and put a flashlight on you,” he said.

He was graduated on a Friday and returned to New York City to start working for AP the following Monday. He stayed there for 12 years.

When asked about the best story he ever wrote, he answered quickly: “The best story was never published. It was my first week on the job. I was on the New York docks in June 1945. Troops were coming home by the tens of thousands every day. I had to go to each ship I was covering and get the manifest — the names of all the men aboard and their hometowns. And I had to get feature stories. I spoke to a handsome, big, tall Air Force captain with a silver star. He said: ‘God damn Russians had me as a prisoner for a year.’ He piloted an Air Force bomber out of Italy to bomb oil fields in Romania; the Germans were using them. The captain said the plane was hit and didn’t have enough fuel to return to base. He went to Russia, which at that time was our ally and which was much closer, and landed. ‘The Russians took me and my crew to a house up on the hill, where we could see what was going on. They dismantled the plane piece by piece,’ ’’ he said.

He told his bosses the name of the captain and the name of the small town he was returning to in Maine, but they didn’t want to pursue a story.

He tells other stories with the same ease.

He was working by himself on Saturday, July 28, 1945, when a US. Military plane crashed into the Empire State Building, killing 14 people. “I had not had enough time to learn the AP Stylebook. All the bigwigs were standing around me. I had headphones on and was typing like mad. The chiefs kept pulling paper out of the typewriter before I could finish a sentence.”

That propelled his career. That following Monday, Blackmon told him that reporters had to have five years’ experience to be considered for a job in New York. But Blackmon said he could place Alexander in the “boonies.” Alexander accepted and moved to Charlotte, N.C. “I went there as an editor. That’s where I met my wife. She was a cashier at a well-known restaurant in Charlotte. Then I went to Raleigh, where I was a state capital correspondent for nine years. It was a great job.”

He and Josephine, whom he calls Jo or Josie, have been married a mere 72 years. They live in Bethesda, MD.

He left the AP and in 1957 became deputy information officer for the Panama Canal operation, which included the Panama Steamship Line and Panama Railroad. He worked there for seven years, serving as the liaison between the governor of the zone and the mayors of the Canal Zone community, writing speeches, escorting VIPs and leading goodwill tours to the interior.

Before leaving the Panama Canal Zone in 1963, he and Jo adopted two daughters, the first in Raleigh, N.C., and the second in Panama. Both live within 20 minutes of their parents.

His next stop was heading the information program for the Division of Accident Prevention in the U.S. Public Health Service in Washington, D.C. At that time, there were more people in hospitals from accidents than disease, he said. “We spent a couple million research dollars to help develop what we now call the seat belt. They had just started making sliding glass doors, and people were walking into doors, bleeding. Rotary lawn mowers — they didn’t figure on the trajectory of stones they might hit. Our program staff did a great job in making manufacturers safety conscious.”

The list of new inventions with unintended consequences turned what could have been a routine job into a tremendous one with a great boss, he said.

After a year, Alexander started work as a public information officer at the U.S. Department of Education, which was trying to desegregate schools as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. His job as chief of information for desegregation was “an impossible job with too many voices telling me what to do. I could only do so much.”

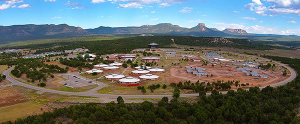

But he remained with the DOE in various roles until he retired in 1985. When he was assigned to the assistant secretary for adult education, he and his boss went to the Navajo Indian reservation, where they were trying to establish a “real” community college. When they got there, they found two double-wide trailers — that was the community college. “My boss had quite a bit of money he could disperse. We went out there, and he and I were treated like kings. They now have a very lovely community college.”

Alexander said his health is good, but he can’t walk as far as he once did.

He has donated regularly to the University of Florida, starting in 1971 with a gift to the Alumni Association. For the last six years, he’s supported the Friends of the Panama Canal Museum, which has a collection in Smathers Libraries. He has set aside his personal collection of Panama Canal memorabilia to donate after his death.

And that could be a while. Alexander has no intention of slowing down anytime soon.

Posted: April 30, 2019

Category: Alumni Profiles, Profiles