Associate Professor of Journalism

The University of Florida

The hotel phone rings at 4:52 a.m., and Joel Sartore

says he's ready to go. "You up, John? Meet me in the

lobby." I head downstairs and stare out into the

darkness of Lincoln, Neb.

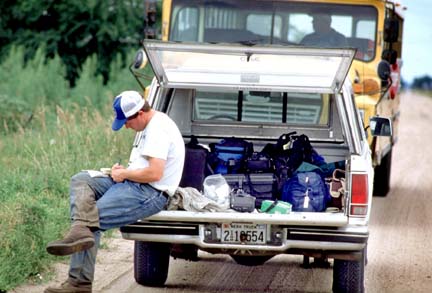

At 5:02 a.m., a white 1989 Chevy pick-up arrives and I

stumble out to greet Sartore, who's guzzling a cold can

of Coke. Driving his dad's former fishing truck, Sartore

is shooting a feature spread on Nebraska for National

Geographic. I'm going to be his assistant for two

days.

During the previous seven weeks, as the recipient of the

photographic division's summer faculty fellowship, I

walked the halls and poked my head into offices at the

magazine's headquarters in Washington, D.C. Now I'm out

in the field to further observe how one of the world's

top magazines gathers its photographs. The fellowship is

a far cry from my regular job overseeing the

photojournalism sequence at the University of Florida.

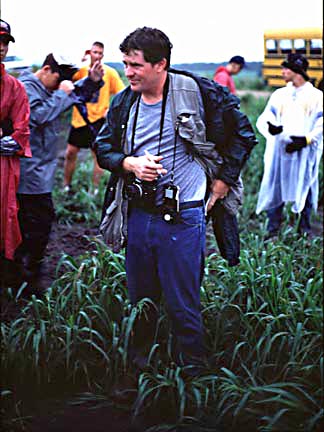

It's cold and rainy and still dark as we drive toward

Seward, Neb., where a crew of middle schoolers is

detassling corn. Wearing maroon ponchos, they wade

through the mud, breaking off the seed part of the corn

to keep the hybrids pure. By dawn's gray, even light,

Sartore shoots through the rain-drenched stalks of corn.

The students' work is monotonous and tiring and messy,

and Sartore emerges sweaty and disheveled on the far side

of the field. Cracking a wry smile, he tells me:

"I'm going back in." I had already reviewed

some of Sartore's Nebraska project earlier in the summer.

Batches of film are routinely shipped to Washington for

processing. I knew that Sartore would see things in that

wet cornfield that I wouldn't. I knew his viewpoint would

include a touch of quirkiness. But the one thing I didn't

know was that we'd seldom stop, except for three meals a

day at McDonald's (always eaten in the truck).

Geographic photographers are known to shoot

early and late in the day, and sleep during the

afternoon, but our hectic pace continues from sunup until

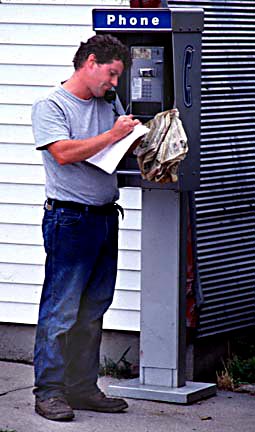

past sundown. Sartore uses afternoons for travel and

phone calls. He figures 40 percent of his time is spent

researching what's meaningful to shoot. Maps and yellow

notepads with names and numbers clutter the inside of his

truck.

Unlike most freelance magazine photographers, Geographic

shooters construct the story line as they see it from the

field. They receive some guidance from editors, but are

expected to have a thorough sense of an area's history,

economics and social structure. Typical assignments in

the past used to stretch to six months, but now many are

limited to six weeks. Since Sartore lives in Nebraska,

this project was being shot off and on over a year and

half. "It's still one of my favorite stories,"

Sartore says in retrospect. "It was really nice to

sleep in my own bed for a change. They never had to buy

me plane ticket."

The corn detasslers finish their job by early afternoon

and Sartore wants to ride back in the school bus with the

tired group. I follow along through a rainstorm in the

white pick-up, wondering what adventure is next.

We head for Western, a tiny town with a four-way stop in

the heart of downtown. Sartore wants to check out a

scenic life-size 1909 mural, hoping to photograph

pedestrians who will seem to blend into the painting. A

Founder's Day parade brings lawn chairs out to the curbs

of Main Street, and I lose sight of Sartore. Minutes

later he comes riding by on the back of a homemade float,

photographing a man wearing a Richard Nixon mask.

Sartore shoots the carnival rides and bingo games

throughout the golden light of twilight, then we drive on

to Grand Island. The Holiday Inn seems to be hosting a

high school cheerleading clinic that has spilled into the

hallway outside our rooms. It's 10:20 p.m.

Sartore has located a second group of detasslers using a

type of people mover in the fields, so Day 2 begins near

Chapman (pop. 272) at 6 a.m. The ground is muddy here

too, but the light is bright and strong and the sky is a

brilliant blue. "Hi. I' m Joel from National

Geographic and we're doing a story on

Nebraska," Sartore tells every group before he

starts shooting. The students mug the camera for a few

minutes then forget him. Having moved to Nebraska at age

2, Sartore considers himself a native. His parents and

in-laws live nearby.

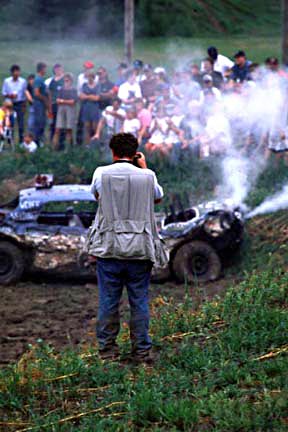

By 3 p.m. that Sunday, we're far away from the

detasslers. We arrive in Bloomington for a demolition

derby. It's hot and still, and the bleachers around a

large embankment are full of spectators waiting to see

which car can smash and be smashed and still run at the

end. One of the top prizes is a rifle. The noisy

spectacle reeks of gasoline fumes and burned oil. The

championship round is over by 5 p.m., but Sartore wants

more. We head for a bigger derby in Fairbury. The

grandstand there shades the field and it gets darker as

Sartore shoots until almost 9 p.m. Finally, we head back

to his hometown of Lincoln. I drive part of the way while

he scribbles down caption information and labels 45 rolls

of film for shipment.

Sartore is modest about his work that often results in

prize-winning photographs or book covers such as the

recent One Digital Day. Referring to the

demolition derbies, he says, "Anyone with an 80-200

standing where I was could've shot the same

pictures." He credits both his University of

Nebraska photo professor, George Tuck, and his first

boss, Steve Harper of The Wichita Eagle, for

suggesting he work on projects instead of just hunting

for single features.

On my final morning in Nebraska I invite myself out to

see Sartore's latest personal project: a two-story

Victorian farmhouse sitting on 20 acres of land eight

miles outside Lincoln. He and wife Kathy have plans to

restore it to a home with more than 3,000 square feet and

modern upgrades like heating, cooling and indoor

plumbing. But with a second child now and Sartore gone so

often on assignment, they've decided it's best to move

back into town during fall 1998.

My weekend as an assistant was a bonus, not a guaranteed

part of the fellowship. It did provide valuable insight

into the pressure of shooting for National Geographic,

and reinforced my respect for the long hours and

dedication it takes to succeed.

(Copyright 1998, by John Freeman)

Originally published by the National Press Photographers

Association and

News Photographer magazine, October 1998. To see Joel

Sartore's finished article on Nebraska, see the November

1998 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Special thanks to Tom Kennedy and Kent

Kobertsteen for the fellowship award and their

hospitality during the summer of 1996.